As all English majors know, there are dozens of different ways to analyze literature. You can pick apart a book based on when it was written, or by whom. You can look at how the book treats women and people of color, and you can spend your life arguing about whether or not that (often shoddy) treatment was intentional. You can compare any of those characteristics to those of another author. You can even compare an author to himself.

Kurt Vonnegut has been analyzed in all these ways, but he may never have been analyzed the way journalist Ben Blatt does it: by the numbers. Blatt’s recent book, Nabokov’s Favorite Word Is Mauve, examines dozens of classic and bestselling authors using that so-called nemesis of English majors: mathematics. But Blatt presents his information well, and the charts and graphs provided are helpful and clear. Let’s take a look at how Vonnegut’s word usage and sentence structure compare to other authors.

Let’s start by judging Vonnegut by the most revered writing guide of all time: Strunk & White’s The Elements of Style. Vonnegut himself highly recommended the book in his essay “How to Write with Style.” Its rules of thumb include avoiding adverbs ending in –ly and eliminating the word “not” from one’s vocabulary.

Vonnegut did a pretty good job of keeping the word “not” out of his work. He only uses the word “not” on an average of 77 times per 10,000 words, putting him in the bottom fifth of Blatt’s sample of 50 classic and contemporary authors. His –ly adverb usage also isn’t too bad. In a sample of 15 authors’ –ly adverb usage, Vonnegut, with a rate of 101 adverbs per 10,000 words, ended up in the bottom third. (To put things into perspective, the sample’s greatest adverb avoider was Ernest Hemingway, and its greatest adverb abuser was E L James.)

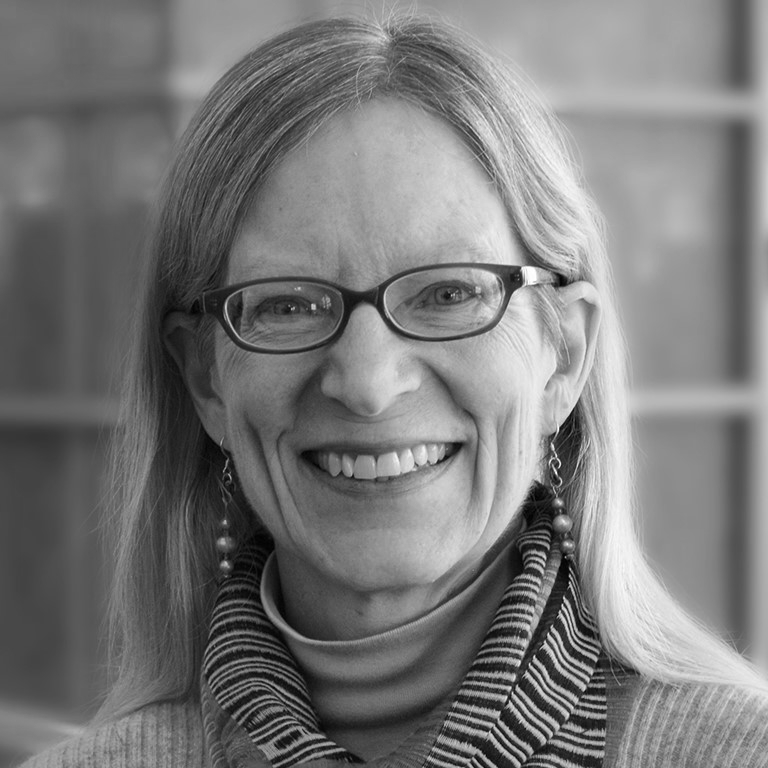

Now let’s talk pronouns. Specifically, “he” and “she.” Like almost all of his male colleagues, Vonnegut is a habitual “he” user. He uses “he” more than “she” in every one of his novels, and Slaughterhouse-Five uses “he” 84 percent of the time. 13 percent of the 50 male-authored books Blatt surveyed used “he” 80 to 90 percent of the time, and 7 percent used it 90 to 100 percent of the time. The 50 female authors surveyed were much different; the only one who used “he” more often than Vonnegut did in Slaughterhouse was Willa Cather in Death Comes for the Archbishop.

Half the he-she comparison chart in Blatt’s book. Slaughterhouse-Five is featured in the bottom third (just 3 slots above the lowest purple).

Why does Vonnegut use “he” so much? Simple: his books tend to star men. Not that there aren’t women, of course, but they are rarely, if ever, major characters. In the case of Slaughterhouse-Five, this makes sense; a war zone in the 1940s would naturally have been composed mostly of men. But this doesn’t explain away the rarity of female main characters in Vonnegut’s other books.

Or maybe it does. In another study, Blatt considers the words authors use the most in their work. He calls these words “nod words” after author Michael Connelly’s near-constant use of the word “nod.” To qualify as a “nod word,” words have to be used in every book by a particular author at a rate of at least 100 for every 100,000 words. It also can’t be a proper noun or an extremely obscure word. This rules out words specific to a particular fictional universe, like Harry Potter’s “Muggle.” One of Vonnegut’s “nod words” is “said,” which tells us hardly anything except that his books have a lot of past-tense dialogue, but another is “father,” which may hark back to Kurt’s strained relationship with his own father. Another is “war.” Vonnegut’s books do usually have some kind of war caught up in them, whether it’s being fought during the story or not. Could Vonnegut’s understanding of wars and how they’re fought explain why he tends not to put women in starring roles? Maybe, maybe not.

So far we’ve just looked at individual words. How about sentences? This is where Vonnegut becomes more of an outlier. As most Vonnegut fans could guess, the most frequent sentence used in any of his novels is “So it goes” from Slaughterhouse-Five. It’s used 106 times, which is more than once every three pages. What’s more, it’s used more often than any other sentence in any other work in Blatt’s sample of 50 well-known authors.

Vonnegut also uses anaphora constantly. Anaphora is a literary term describing repetition of a word or group of words at the beginning of a sentence. For the purposes of his study, Blatt defined anaphora as a sentence starting with the same word or the same two words as the sentence preceding it. In Blatt’s list of books from his sample with the highest one-word anaphora, three were written by Vonnegut: Breakfast of Champions, Slaughterhouse-Five, and Slapstick. On the list of works with the highest use of two-word anaphora, two works were by Vonnegut: Slapstick again and The Sirens of Titan.

According to Blatt, two-word anaphora is more likely to be intentional than one-word. This passage from Cat’s Cradle, cited by Blatt in the book, is a clear example of intentional two-word anaphora:

Before we took the measure of each other’s passions, however, we talked about Frank Hoenikker, and we talked about the old man, and we talked a little about Asa Breed, and we talked about the General Forge and Foundry Company, and we talked about the Pope and birth control, about Hitler and the Jews. We talked about phonies. We talked about truth. We talked about gangsters; we talked about business. We talked about the nice poor people who went to the electric chair; and we talked about the rich bastards who didn’t. We talked about religious people who had perversions. We talked about a lot of things.

Not all of Vonnegut’s anaphora is this extreme, but it’s still a constant presence in his work. There are 87 instances in Slaughterhouse-Five where 3 sentences in a row begin with the same word. Here’s a list of the 10 most common 3-word sentence openers in Slaughterhouse-Five:

1. So it goes

2. There was a

3. It was a

4. And so on

5. He was a

6. He had been

7. He had a

8. They had been

9. One of the

10. Now they were

What would Vonnegut have thought of this numbers-oriented analysis of his work? Well, he did write a master’s thesis about mapping stories as curves on graphs (to watch him explain it, go to this site), so he may well have been interested in studying literature using numbers. We at KVML know we are.