On Censorship and Freedom

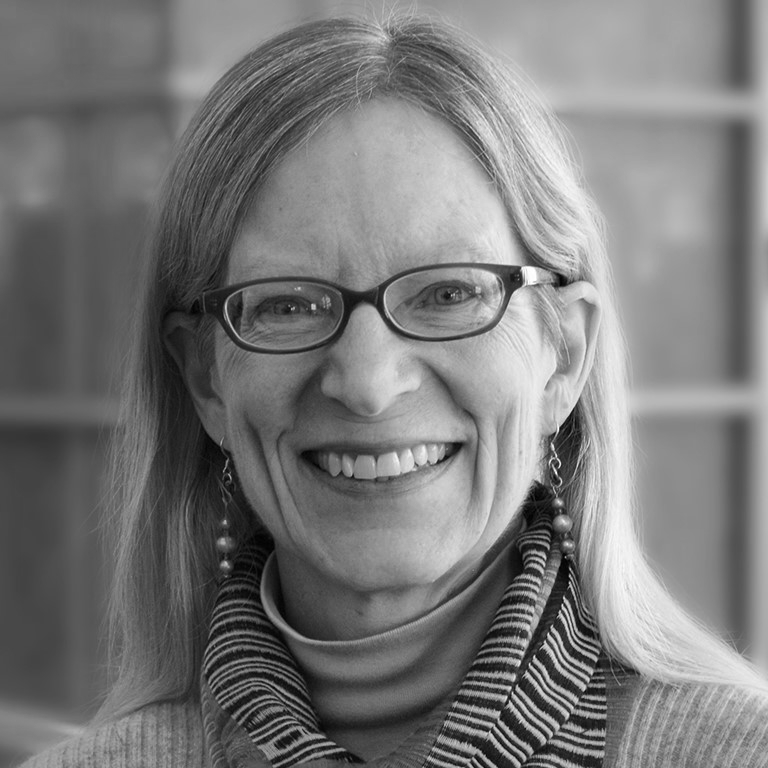

By Rai Peterson, BSU English Professor and Banned Books Week Prisoner

At the start of this semester, I met a new graduate student from the Middle East in my office. He is new to our department, and I was getting to know him a bit, asking about his family, his homeland, his decision to come to Indiana to further his education. He told me that his parents had great trepidation about his traveling to the USA because people in his Muslim homeland believe that there is pornography on the streets in America.

“Naturally,” I said, apparently with evident sarcasm, “we might give that impression through our recent news.”

The student sprung to his feet and quickly closed my office door. “The walls may have ears!” he whispered. His country is notoriously sensitive about criticism of its government’s human rights violations.

“Probably not, “ I replied, “in the U.S.A., criticizing the government is our political duty as good citizens.”

“With respect,” he corrected me, “it’s not you I’m worried about. If I learn American habits of criticizing rulers, I could be killed when I go back home.”

Let. That. Sink. In.

Fast forward to my being interviewed about serving as the Banned Book Week Prisoner at the KVML. The journalist was from a country where book banning occurs frequently. He lobbed a few questions about my involvement with the KVML, our students’ projects there, and Banned Book Week events.

Then he hit me with the clincher: “Why do you feel it is necessary to protest book banning in a country where it seldom happens, and never, really, on a national level?”

He is correct. By international standards, the U.S.A., with its freedom of the press, is without widespread censorship. Of course, we have the occasional school-system-wide book banning, Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five is subject to such local prohibitions. Yet, in recent history, books that are critical of governments or even salacious have not been banned across our country.

So, why do we continue to protest book banning in the United States of America? The short answer is: because we can. The First Amendment, the first among the first ten amendments which are also called the Bill of Rights, says:

Literally, this means that, as long as it is true and hurts no-one, Americans can believe, say, or print anything, and that they can gather to agree or disagree about that, and, furthermore, that they can sue the government when it acts wrongly. This is remarkable. It is our greatest collection of freedoms. But society, as well as the government, decides who can speak and who can be heard.

Just this week, a public figure from the world of entertainment was sentenced to prison for sexually assaulting a woman fourteen years ago. She and dozens of other women have repeatedly spoken up about his illicit use of drugs, force, and power, yet it has taken years of their persistent chorus to bring about this limited justice. Their testimony has been dismissed because he is a rich, powerful—and even because he is a funny—man.

We’ve seen echoes of this throughout the entertainment and government world, including the testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee this week. Everywhere, it seems, people are asking why victims don’t come forward with damning evidence against powerful men, even men whose power derives only from their gender, sooner.

Shut. The. Front. Door.

One reason victims don’t come forward is that they don’t believe they will be heard.

In our country, it’s not the walls’ ears that we must to worry about. It’s our own.